Roald Amundsen below decks on the

Maud1918-20

Roald Amundsen - 3

Northeast Passage, Maud - 1918-1925

1 - Belgica,

Belgian Antarctic Expedition,

1897 - 1899 - 1st Mate

& Gjoa,

Northwest Passage, 1903-06

- Captain

2 - Fram,

South Pole Expedition,

1911-12 - Expedition Leader

3 - Maud,

Northeast Passage, 1918-25

- Expedition Leader

4 - N24 and N25 Flying

Boats,

North Pole by Air, 1925

5 - Airship Norge,

North

Pole by Air, 1926

6 - The last years

and last journey

to 1928

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen - 16th July 1872 - 18th June 1928

The Northeast Passage

Amundsen built a new ship he named the Maud after the queen of Norway for this purpose as the Fram was now unseaworthy after a few years in warm southern waters which had rotted the hull. The new ship was similar in design to the Fram, very strongly built with a rounded bottom to rise up if trapped by ice rather than be crushed by it. At its launch Amundsen christened the ship by breaking a piece of ice against the bow rather than the traditional champagne bottle. For the first time he had a scientific programme and the ship had a geophysicist amongst her crew of nine, there were four men from the South Pole expedition, Helmer Hanssen, Oscar Wisting, Knut Sundbeck and Martin Ronne, Amundsen was now 47 years old.

The Maud at Maudhavn on the 17th

of September 1918, the day she froze into the ice for the first

winter

The Maud left Oslo on midsummers day 1918, the last landing in Norway was at Vardo on the 18th of July and she met the first ice four days later, it was a difficult ice year and along with stormy weather and a grounding, progress was not made as hoped, though they matched Nansen's schedule. On the 31st of August they reached Dikson in Russia, the last telegraph station, by the 17th of September they were iced into a small sheltered bay as their winter harbour that Amundsen called Maudhavn. Harald Sverdrup, the geophysicist soon set up a magnetic observatory and his meteorological instruments.

The Maud prepared for winter, 1st

November 1918, note the snow blocks piled up around the ship

to keep out the wind and add insulation to the living quarters

onboard

The First Winter - 1918-19

Amundsen had a winter beset by accidents, (despite his claims that bad luck was simply the result of bad planning). He fell through the sea-ice and was saved by Hanssen. While carrying a dog down the ship's gangplank for his morning walk another dog bumped into him causing a heavy fall onto his right shoulder breaking a bone, he remained in his bunk for eight days following this debilitated by pain. His arm still in a sling from this injury some six weeks later, he followed a curious dog into the fog near the ship, a series of eerie sounds ensued with the dog running back followed by a polar bear which then ran after Amundsen as he tried to reach the safety of the ship. The bear caught up with him and began mauling him until a dog arrived and took its attention away, Amundsen had sustained a sprained wrist and number of gashes that needed stitching, he was saved from worse by his heavy winter clothing.

The next accident occurred in the magnetic observatory, a simple one room hut with no window, lit and warmed by a kerosene lamp. Amundsen had become engrossed in his work and didn't notice that he was feeling drowsy and disoriented and that his heart was racing, he could barely stand and just managed to get out of the hut before he became unconscious. He had succumbed to carbon monoxide poisoning from the lamp. His heart beat erratically for days afterwards and even months later mild exercise could send his heart into irregular rapid beats, it would be years before the effects eventually subsided, they were probably permanent. As a result of Amundsen's injuries he couldn't take part in sledding expeditions which were left to the other men, he became the expeditions cook instead.

Summer came late in 1919 and it wasn't until the 12th of September that the Maud was released from the ice to continue her expedition. The carpenter, Peter Tessem wanted to leave the expedition due to headaches, sleeplessness and melancholy, Paul Knudsen volunteered to accompany him and take the scientific data so far gathered back to Norway via the outpost of Dikson 650km away. They were left on shore in a small cabin when the ship left to wait until conditions were right for travelling. Both men were experienced travellers and hunters familiar with Siberia, they had six dogs and a years provisions along with the scientific results and mail. They were never heard of alive again. Some years later the remains of Tessem were found near to the Dikson meteorological station, it is thought that Knudsen died first through some mishap and that Tessem continued alone getting very close to his goal before possibly slipping on the ice, knocking himself out and freezing to death. The remains were buried where they were found and the grave marked.

The Second Winter - 1919-20

The Maud made progress for just eleven days before she was once again stopped by ice and found a new winter harbour near Ajon island near the mouth of the Kolyma river. It was a demoralizing step, just eleven days progress in a year to find themselves in very similar conditions to where they had spent the previous winter. A group of Chuckchi people had made a winter camp site nearby, little was known about them at that time and they lived almost completely separate from the Russian state and people. Harald Sverdrup joined some of the group and travelled with them for over seven months across Siberia learning about them and their culture from which resulted a detailed book of their way of life.

Three of the crew were sent on a three week round trip by dog-sled to Nischne-Kolymsk to report to the authorities on the presence and location of the Maud, this was shortly after the Russian Revolution and Amundsen was concerned that some difficulties could arise otherwise. On December the 1st another three were sent by Amundsen on a journey to the telegraph station at Nome in Alaska to deliver post and send a telegram to the press. It wasn't possible to cross the Bering Strait to Alaska so Hanssen skied alone with his sled and dogs to Anadyr from where the messages were sent. Two of the three man party arrived back at the Maud in June 1920 after a six month trip covering 1,000km, the third man Tonnesen decided to leave the expedition and returned to Norway.

Roald

Amundsen with Marie the polar bear cub in May 1920

Roald

Amundsen with Marie the polar bear cub in May 1920

At the end of May 1920 the crew came across a polar bear cub which they took on board and named Marie, she was looked after by Amundsen, though was put down a month later when she grew too large and dangerous.

Amundsen now decided he would sail for Nome when the ship was released from the ice which happened on the 8th of July. On the 15th of July the ship cleared the Northeast Passage, only the third to ever do so and making Amundsen and Helmer Hanssen the first to sail both the Northwest and Northeast passages, they reached Nome on the 25th of July 1920.

The Third and Fourth Winters - 1920-22

At Nome another three men left the ship, Amundsen, Wisting, Sverdrup and Olonkin remained. They had been away for two years much of which was spent not moving with no progress made towards the north pole, one of the main purposes of the expedition and all this experienced with the ever present backdrop of potential danger. The prospect was of a further undetermined length of time but probably a few years, and then with no particular notable "first" or discoveries to come from it, morale had been low on the ship.

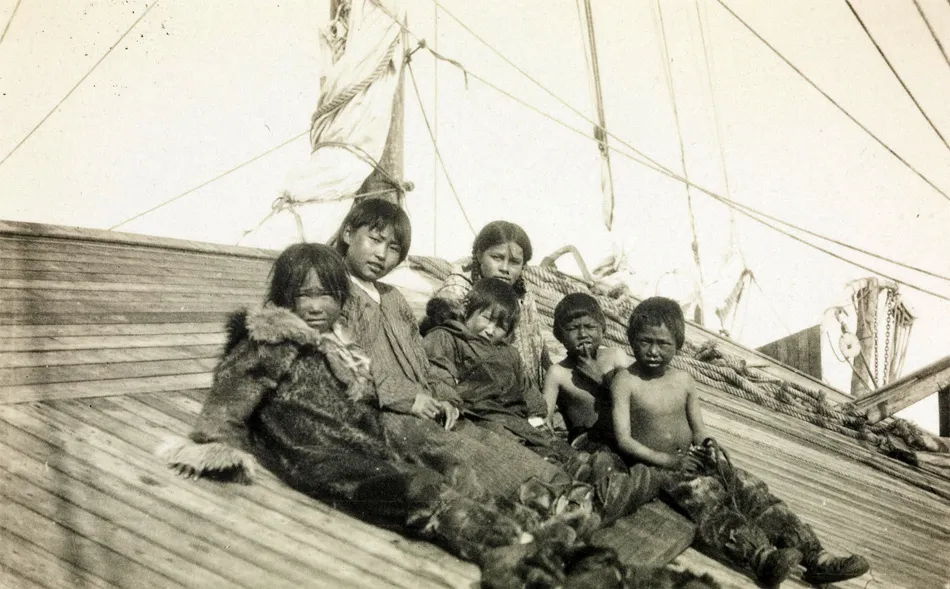

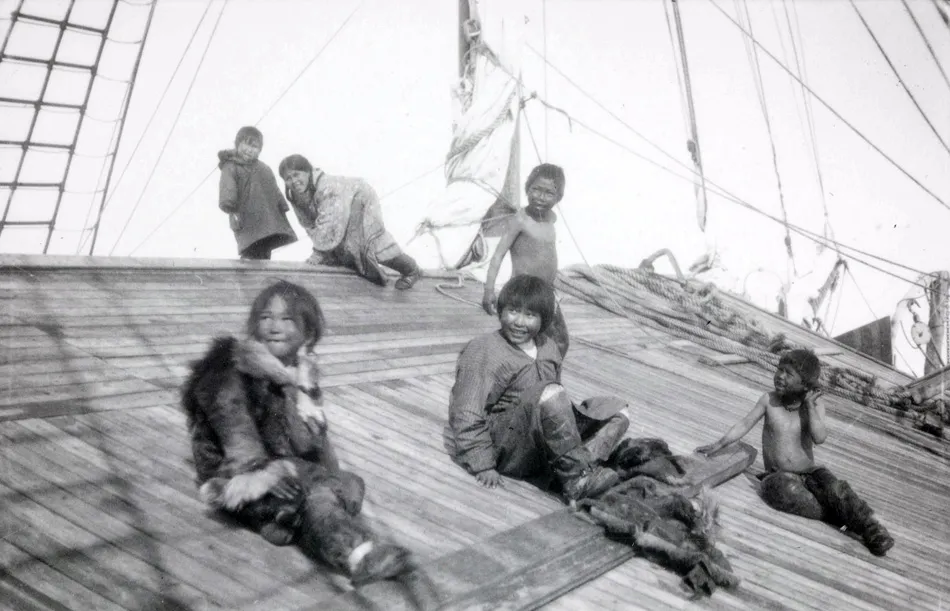

Chuckchi children playing on the

Maud, 13th of May 1921

After ten days in Nome now with an Inuit cook the crew called Mary, the Maud headed north again and before very long, once again the ship was iced in at just 76 degrees north. The ice pushed the Maud towards the Siberian coast rather than taking her towards the pole as hoped, she suffered damage to her propellers from the ice and and a trip would have to be made to Seattle for repairs. Once again a encampment of Chuckchi was nearby and Amundsen ended up looking after an unwell four year old girl called Kakonita whose mother had died when she was essentially abandoned by her father. In early 1921 Sverdrup and Wisting went on a 10 week, 2,000 km sledging trip around the Chukchi Peninsula.

Frustrated by events and a lack of progress Amundsen left the ship by dogsled with Kakonita to head to a Russian port where he took a boat to Nome and on to Seattle arriving in July 1921. Back on the Maud, Wisting hired six Chuckchi to help sail her to Seattle leaving the ice behind in June, they were towed 400km by an American ship and arrived on the 30th of August, she remained there for the winter while she was repaired with a crew of two.

Amundsen was received well in Seattle appearing at many public events, while there he learned from his brother in Norway that the Norwegian government had voted to donate a large sum to repair and overhaul the Maud which relieved him of financial worries for the time being. He spent the summer and autumn of 1921 touring Seattle with Kakonita and another girl, Camilla the 9 year daughter of Clarendon Carpendale and his Chuckchi wife as a companion for her. He acted as guardian for the girls and took them to Norway with him in January 1922, placing them in school where they stayed for two years.

He did his best to monetize his expedition so far selling things he had collected such as mammoth teeth, bird specimens and furs and wrote a book that was only published in Norwegian. The expedition had already lasted longer than expected and didn't have the potential for much more success, Amundsen however decided to revisit his plans of flying to the pole that had been thwarted by the continuing war back in 1917/18.

Flying to the Pole - 1922-24

By May 1922 Amundsen was back on the Maud with eight other crew members five of whom were new to the ship including a meteorologist, two pilots and a machinist. His new plan was to inject some life into his expedition by flying from Point Barrow in Alaska to Spitsbergen via the north pole, the Maud would attempt to sail a similar route but without him on board. It was an attempt to raise more money for the expedition while indulging his love of flying, a scientific reason was also touted as Amundsen claimed that the poles were "climate makers" and his findings on the flight would be of great value in charting and predicting the weather of all northern lands.

The small Curtiss aircraft (Kristine)

being prepared for flight May 1923

He had bought a large German Junkers aircraft in New York while on his way back to the ship that he and Oscar Omdal one of the pilots were to fly to Seattle though it crashed early in the journey in Pennsylvania. Another similar plane was packed up and shipped to Seattle along with a smaller American Curtiss Oriole given as a gift by the manufacturer hoping for publicity. Both were loaded onto the Maud in several crates on deck which made her unwieldy and unbalanced so Amundsen took a passenger ship to Nome where he joined the Maud. He named the large Junkers Elizabeth and the smaller Curtiss Kristine after the Norwegian wife of a wealthy Englishman he had been pursuing an affair with for several years.

The larger Junkers aircraft (Elizabeth)

being prepared for flight May or June 1923

The smaller plane stayed on the Maud to scout the ice around the ship while the larger Junkers was transported on a supply ship to Wainwright Alaska with Amundsen and Omdal. The Maud froze into drifting ice near Wrangel Island with Wisting as captain though once again the current didn't take them anywhere near where they hoped. Two flights from the Maud were made in May 1923 with the small Curtiss plane which crashed on its second flight writing it off.

Amundsen and Omdal spent the winter of 1922-23 in Wainwright Alaska, they built themselves a two bedroomed house and a crude hanger for the Junkers as the weather had stopped any attempts at flying later in the season. Amundsen went on an overland journey to Nome in the south against the advice of a doctor who had told him to avoid strenuous exercise due to his carbon monoxide poisoning in the first winter of this expedition, instead he took great delight in showing himself to be fit and still able. He spent most of the winter in Nome enjoying his fame and popularity. At this time he had to address the problem of financing to some degree, though the reality of doing so was something Amundsen had largely avoided in the past relying on others (mainly his brother Leon) to deal with the dreary details while he ran up costs expecting that something would happen to pay them in the future. He was now effectively running two expeditions with the funding for just one, the original Maud voyage and now an audacious flight across the arctic via the pole, at the time Amundsen was the first to fly at all in the arctic region. Selling a property he owned in Norway kept his creditors at bay for the time being.

Blanket toss, Wainwright

Alaska, 1922-23

Amundsen arrived back in Wainwright by dogsled in May 1923, Omdal had prepared the Junkers during the winter with skis instead of wheels. On May the 11th the engine was fired up and a short test flight made, all went well until the landing when the left ski crumpled on contact with the ice and the aircraft scraped a wing causing some significant internal structural damage. Closer inspection found a fundamental flaw in the construction of the aircraft that made it poorly suited to the impact of landing on skis. Omdal was blamed initially though the answer was there were several possible opportunities to have avoided this situation, the manufacturers could have been asked about suitability or they could have volunteered information or Amundsen himself could have tested properly before use. In an earlier time he might have described such a failure by others as failure to plan fully. Another attempt was made a month later on June the 10th with a similar result and the scheme to fly over the pole was called off.

Later in 1923 Amundsen's finances and reliance on others to look after those aspects of his affairs he found dull began to catch up with him. He went to Norway in November to a frosty reception. The Maud expedition had been underway for over 5 years with the chief advertised aim no nearer to completion now than at the beginning, men had come and gone, extra government funds spent and Amundsen himself had long since left the ship to move onto a different expedition by air which had quickly failed. The mismanagement of the whole affair while Amundsen travelled back and forth across America and to and from Norway was seen as a bad investment. Also during this time Amundsen intermittently had two affairs with married women, one in England and one in Alaska which it seems had dictated to some degree where he was at various times and why he was there.

Amundsen had appointed a man called Haakon Hammer to whom he had given power of attorney and control of his business affairs. Hammer had come up with some good ways of making money from the would-be flight, 10,000 "Trans-Polar Flight Expedition" postcards at $1 each to be carried and delivered by Amundsen in his Junkers (sold but never delivered) along with deals with magazines, newspapers and film rights. Meanwhile Amundsen travelled to Italy to purchase three Dornier-Wal flying boats at $40,000 each ($605,000 at 2020 prices) still determined to make his polar flight, Hammer assured him that finances would be in place for the purchases in early 1924. The reality was that there were no funds to pay for the aircraft, Amundsen was forced to publically announce the flight would be indefinitely postponed. His expedition had come to an end and there was no way of paying the debts incurred, by September 1924 he was bankrupt and being criticized heavily in the press.

Wisting received a message from Amundsen to return and they struggled through the Bering Strait to arrive at Nome, Alaska in August 1925 after a further three years in the ice. She was taken and sold to the Hudson's Bay Company to pay off debts, she was frozen into the ice at Cambridge Bay in 1926 and sank in 1930.

In 2011 a project began to raise the Maud, she returned to Vollen, Norway (where she was built) in August 2018.

18th August 2018, the salvaged Maud

arrives back in Vollen, Norway.

Next page - to the North Pole by flying boat

Historical pictures from Nasjonalbiblioteket / National Library of Norway, link

Picture of Maud in 2018 used courtesy of Svend Aage Madsen under CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

Roald Amundsen Books and Video

The South Pole:

Roald Amundsen, the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition, 1910-1912

The Last Viking:

The Life of Roald Amundsen

Roald Amundsen's Sled Dogs:

The Sledge Dogs Who Helped Discover the South Pole

Roald Amundsen

The Quest for the South Pole, ages 9-12

The Amundsen Photographs

discovered in 1986, pictures from three of Amundsen's voyages

Roald Amundsen Explores the South Pole

ages 7-10