How do Penguins Keep Warm?

Science of the Cold

How do penguins survive and thrive in the coldest climates? Being warm blooded they must keep their body temperature constant.

Be Big

Warm blooded animals in cold climates are pretty large, even the smallest Antarctic birds are on the large side and the smallest Antarctic penguin, the Rockhopper is a fairly hefty 2.5kg (5.5lb). The Adelie and Emperor penguins of the deep south are larger still. Adult weights are 5kg (11lb) for the Adelie and 30kg (66lb) for the Emperor - a similar size to an overweight 10 year old child, but with a man-sized chest measurement.

Large animals have a smaller surface-area : volume ratio and so the less relative area there is to lose heat.

Take a 1cm cube:

![]()

-

Volume = 1 x 1 x 1 = 1cm3

Surface area = 6 faces x (1 x 1) = 6cm2

So for 1cm3 of volume there are 6cm2

of surface area to lose heat from, 6 / 1 = 6cm2

per 1cm3

Surface-area : volume ratio

is 6:1

Now take a 3cm cube, identical shape:

-

Volume = 3 x 3 x 3 = 27cm3

Surface area = 6 faces x (3 x 3) = 54cm2

So for 27cm3 of volume there are 54cm2

of surface area to lose heat from, 54 / 27 = 2cm2

per 1cm3

Surface-area : volume ratio

is 2:1

If you imagine these are simple cubic warm-blooded animals, then the small cube has 3 times the surface area per unit of volume compared to the large cube.

If each of these are both warmer than the outside temperature, the small cube will cool down much more quickly.

Somewhat surprisingly, it doesn't matter what the shape is, the principle stays the same for all geometrically identical shapes - including animal shapes. This means that for identically shaped animals of different sizes, the large one will always keep its temperature more easily than the smaller one.

Being bigger means being warmer

Wrap up warm and conserve heat

Penguins

have feathers to keep them warm right? - Partly right,

feathers work on land, but in the water where penguins spend

quite a bit of their lives, they're not so good. What really

keeps penguins warm in the sea is a sub-cutaneous (under-the-skin)

layer of fat. This fat layer also serves as a valuable energy

store as we will see later.

Penguins

have feathers to keep them warm right? - Partly right,

feathers work on land, but in the water where penguins spend

quite a bit of their lives, they're not so good. What really

keeps penguins warm in the sea is a sub-cutaneous (under-the-skin)

layer of fat. This fat layer also serves as a valuable energy

store as we will see later.

External fur and feathers are the most efficient insulators on a weight for weight basis, but can be ruffled by wind and are much less useful when wet.

A penguins' fat layer is what protects them against the cold while in the sea. On the land however their feathers fulfill the function of keeping them warm. Penguin feathers aren't like the large flat feathers that flying birds have, they are short with an under-layer of fine woolly down. Penguin feathers are also very good at shedding water when the bird emerges from the sea. They overlap and give a good streamlined effect in the water and excellent wind-shedding abilities when on the land. When it gets very cold, penguins can puff their feathers out to trap more air for even better insulation. When it gets too hot (like as high as freezing point even!) they fluff their feathers out even more so that the trapped warm air can escape and enable the penguin to cool down. Penguins have the highest density of feathers per unit area of any bird.

This fat layer is the best form of internal insulation yet devised by mother nature - and therefore the best way to keep warm in water. It keeps all warm-blooded cold water animals operational down to minus 1.9°C (25.8°F). Why this temperature? - because that's when sea-water freezes, you can't get sea water colder than that without it being solid. A penguin can have up to 30% of its body weight as blubber (fat).

Penguins

have two areas where their body is very poorly insulated and

where they can lose a lot of heat, these are their flippers

and their feet. These regions give penguins at the

same time a problem and a solution. A problem because of the

heat loss, and a solution because they can be used for cooling

down. It's all well and good being brilliantly insulated

when it's very cold, but when you use a lot of energy and

so generate heat, or the temperature rises, not being able to

dump that heat becomes a big problem in itself.

Penguins

have two areas where their body is very poorly insulated and

where they can lose a lot of heat, these are their flippers

and their feet. These regions give penguins at the

same time a problem and a solution. A problem because of the

heat loss, and a solution because they can be used for cooling

down. It's all well and good being brilliantly insulated

when it's very cold, but when you use a lot of energy and

so generate heat, or the temperature rises, not being able to

dump that heat becomes a big problem in itself.

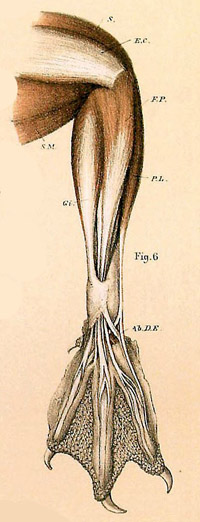

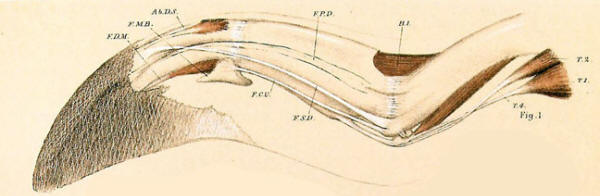

The solution is quite elegant. The muscles that operate feet and flippers are not located in the feet and flippers, but deeper in the warmer regions of the penguins body. The feet and flippers are moved by tendons that pass through them and attach to the bones of the toes, ankle, and wrist like a sort of remote operation by wire or string. This means that it doesn't matter much if the feet and flippers get really cold as they can still be operated normally by muscles in regions that are at normal body temperature and so still fully functional.

Penguins have a heat-exchange blood-flow to these regions called "Rete Mirabile". The warm blood entering the feet flows past cold blood leaving so warming it up in the process and cooling the blood entering at the same time, the same sort of thing happens in the flippers. Blood in the feet and flippers is kept significantly colder than in the rest of the body much of the time. By the time the blood re-enters the rest of the body it has been warmed up and so doesn't have so great an effect in cooling the core body temperature.

Picture above and above left, rockhopper

flipper and leg showing how little muscle there is in the flipper

and foot with tendons which attach to muscles that are deeper

in the penguins body to prevent heat loss

Picture above and above left, rockhopper

flipper and leg showing how little muscle there is in the flipper

and foot with tendons which attach to muscles that are deeper

in the penguins body to prevent heat loss

Penguins feet are never allowed to get below freezing point, blood flow is finely adjusted so that they are kept just above. When it gets very cold, the feet are covered by the feathers and fat layer of the body so they are not exposed to icy winds. So while a man standing barefoot on ice would quickly get frostbitten, penguins can do so all their lives with no damage at all.

At low temperatures or when in the sea, the blood flow to feet and flippers is very low so minimizing heat loss. When the penguin needs to lose heat quickly, the blood flow to these extremities is increased and so lots of warm blood enters them which cools quickly so dumping excess heat rapidly and efficiently.

Some penguins can even be seen to blush pink on the inside of their flippers when waving them around to get rid of excess heat as blood flow is directed to the surface.

Don't touch unless necessary

Ice

and snow are cold. Lying on on snow, you would be really cold

as there would be a large area of contact to lose body heat

though conduction. Stand up and immediately your area of contact

reduces enormously, stand on tip-toes and your area of contact

is reduced to a minimum.

Ice

and snow are cold. Lying on on snow, you would be really cold

as there would be a large area of contact to lose body heat

though conduction. Stand up and immediately your area of contact

reduces enormously, stand on tip-toes and your area of contact

is reduced to a minimum.

This is what penguins do except they don't stand on tip-toes when it's really cold, they rock backwards on their heels, holding their toes up. They stop themselves from falling over backwards by using their stiff tail feathers that have no blood flow and so lose no heat as the third element of a tripod.

Hang around in gangs

Emperor penguins live in probably the most extreme conditions endured by any warm-blooded animal on earth. They even breed in the depths of the Antarctic winter at temperatures of -30°C (-22°F) and below while putting up with winds of 200 kmh (125mph) and more which gives a wind chill factor that you don't even want to think about and that would freeze exposed human flesh in seconds.

Even worse, the emperors breed and overwinter on permanent ice shelves far from open sea where there isn't any chance of being able to feed so the penguins not only endure horrendously cold conditions, but do so with little or no shelter, without feeding - fasting for months - and in the darkness of the long Antarctic winter night.

The males endure the worst conditions looking after the egg on land (or ice) for months on end while the females build up their reserves by feeding at sea. By the time the females return, the males may have lost 40% of their body weight. Relief when it arrives is far from immediate as after the male hands over the egg to the female, he faces a march to the sea that is typically 50 to 100 km, but can be up to 200 km (125 miles). His total period sea to sea before he can catch any live food again living on stored fat can be 115 days or more.

Despite these privations, the emperor penguin maintains a core body temperature at a steady 38°C (100.4°F) throughout. Scientists have worked out that even the great weight loss of stored body fat cannot provide sufficient energy to allow the penguins to maintain their body temperature and so survive the winter, so how do they do it?

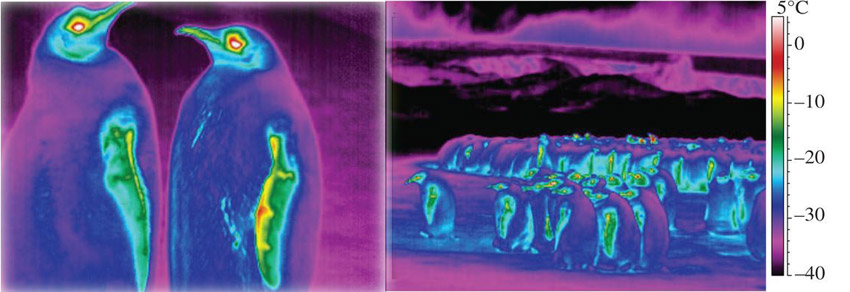

The emperor penguins secret is huddling. Really just an extension of the "be big" method of surviving extreme cold. Emperor penguins have developed a social behaviour that when it gets cold, they huddle together in groups that may comprise several thousand penguins. That way for most of the group, where their feathers end, instead of all of them having to face the biting wind and relentless cold, most of them have another warm penguin to shield them instead. The surface area to volume ratio of the group is greatly reduced and a great deal of warmth and body fat conserved.

Of course it's not quite so great for the individuals on the outside of the group as they only have a part of their body protected and warmed by the other penguins. So there is a continual movement of penguins from the outside of the group to the center so displacing the warmer and more protected penguins to the outside where they will take their turn in the worst places against the wind and raw cold. It has recently been found that penguins in huddles don't quite touch each other as this would compress the feathers and so reduce the insulating layer for an individual, instead, they hardly touch at all or touch as lightly as possible.

Thermal images of

emperor penguins, separate and in a huddle.

Calculations show that a solitary emperor penguin in these conditions could burn up 200g of fat per day to stay warm and alive while huddling penguins need only about 100g per day. Without huddling, emperor penguins just wouldn't be able to breed in the Antarctic winter at all. Young penguin chicks of all species also huddle together for warmth when left behind on the sea-ice by the parents who have to go off fishing for food.

A Summary of how penguins

Thermoregulate

(keep their body temperature

constant)

1/ Overlapping densely packed feathers make a surface almost impenetrable to wind or water. Feathers provide waterproofing in water that is critical to penguins survival in water, Antarctic seas may be as cold as -2.2°C (28°F) and rarely get above +2°C (35.6°F). Tufts of down on shafts below the feathers trap air. This trapped layer of air in the feathers provides 80% to 84% of the thermal insulation for penguins. The layer of trapped air is compressed during dives and can dissipate after prolonged diving, so leaving the insulation to the layer of fat. Like all birds penguins rearrange their feathers by preening.

2/ To retain heat, penguins may tuck in their flippers close to their bodies, this reduces the surface area available for heat loss. They also may shiver to generate additional heat.

3/ A fat layer improves insulation in cold water, up to 30% of a penguins body mass can be blubber, though this is not sufficient on its own to keep the body temperature stable at sea indefinitely in the coldest temperatures. Penguins must remain active while in water to generate body heat. Unlike other warm blooded Antarctic marine animals such as seals and whales, penguins are still relatively small, so the "be big" strategy is not taken as far as needed to remain warm even at rest in the sea as in seals and whales.

4/ Cold climate penguin species have longer feathers and thicker fat than those in warmer climates.

5/ The dark colored feathers of a penguin's dorsal surface (their back) absorb heat from the sun, so helping them to warm up.

6/ King and emperor penguins are able to tip up their feet, and rest their entire weight on a tripod of the heels and tail, reducing contact with the icy surface and so reducing heat loss.

7/ Penguin chicks and adults of some species huddle together to conserve heat. Male emperor penguins will huddle together in groups of up to 6,000 while incubating their eggs during the middle of the Antarctic winter.

8/ Emperor penguins can recapture up to 80% of the heat escaping through their breath thanks to a complex heat exchange system in their nasal passages.

9/ On land and in warmer weather, overheating can be a problem.

i) Penguins can cool down by moving to shaded areas and by panting (like dogs do when they're hot).

ii) Penguins can ruffle their feathers, this breaks up the insulating air layer next to the skin, so releasing the warm air and cooling them down (like opening the front of a coat when you're too warm and wafting it about a bit).

iii) Penguins can increase their heat loss by holding the flippers away from the body, so both surfaces of the flippers are exposed to air, releasing heat.

iv) warmer climate temperate species, such as the Humboldt and African penguins, don't have feathers on their legs and have bare patches on their faces where excess heat can be lost.

10/ Penguins circulatory systems can adjust conserving or releasing heat to keep the temperature constant.

i) To conserve heat, blood flowing to the flippers and legs transfers its heat to blood that is leaving the flippers and legs. This is known as counter current heat exchange and enables the heat to remain in the body rather than ever actually reaching the legs or flippers.

ii) If the body becomes too warm, blood vessels in the skin dilate (get wider), bringing heat from within the body to the surface, where it can be lost. This is a common response in warm blooded birds and mammals, you do it when you exercise and go red in the face or when you blush.

Picture credits, copyright images used by permission: Large top of page picture of emperor penguins - Christopher Michel from San Francisco, Creative Commons 2.0 generic license / Rock Hopper Penguin Feather - Featherfolio, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license / Penguin huddle - Warner Brothers / Underwater penguins - NOAA / Thermal images of emperor penguins - Université de Strasbourg and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Strasbourg, France