Shackleton Endurance Expedition

1914-1917 - Trans-Antarctica

4 - Rescue

1 - departure |

2 - trapped and crushed |

3 - journey to South Georgia | 4 - this page, rescuetime-line & map | crew of the Endurance | the Ross Sea Party

The crossing of South Georgia, rescue attempts for the men on Elephant Island

There was still a major obstacle to overcome. The crew of 6 on the James Caird had landed 22 miles from the Stromness whaling station as the crow flies. In order to get there they had to go across the backbone of mountains that ran the length of South Georgia, a journey that no-one had ever managed, the map depicted the area as a blank.

McNeish and Vincent were too weak to attempt the journey so Shackleton left them with MaCarthy to care for them.

The

mountains of South Georgia that Shackleton, Crean and

Worsley had to cross to reach the Stromness Bay whaling station.

The

mountains of South Georgia that Shackleton, Crean and

Worsley had to cross to reach the Stromness Bay whaling station.

On May 15th Shackleton, Crean and Worsley set out to cross the mountains and reach the whaling station, they crossed glaciers, icy slopes and snow fields. At a height of about 4,500 feet, they looked back and saw the fog closing up behind them. Night was falling and with no tent or sleeping bags, they had to descend to a lower altitude. They slid down a snowy slope in a matter of minutes losing around 900 feet in the process. They had a hot meal with two of them sheltering the cooker from the wind. Darkness fell and they carried on walking, soon a full moon appeared lighting their way. They climbed again and ate another hot meal to renew their energy.

They were soon able to make out an island in the distance that they recognized, but realised that they had taken the wrong direction and had to retrace their steps. At 5 a.m. they sat down exhausted in the lee of a large rock wrapping their arms around each other to keep warm. Worsley and Crean fell asleep, but Shackleton realised that if they all did so, they may never wake again. He woke them five minutes later and told them they had been asleep for half an hour, once again they set off.

There was now but one ridge of jagged peaks between them and Stromness, they found a gap and went through. At 6.30 a.m. Shackleton was standing on a ridge he had climbed to get a better look at the land below, he thought he heard the sound of a steam whistle calling the men of the whaling station from their beds. He went back to Worsley and Crean and told them to watch for 7 o'clock as this would be when the whalers were called to work. Sure enough, the whistle sounded right on time, the three men must have never heard a more welcome sound.

The three walked downwards to 2,000 feet above sea level. They came across a gradient of steep ice, two hours later, they had cut steps and roped down another 500 feet, a slide down a slippery slope placed them at 1,500 feet above sea level on a plateau. They still had some distance to go before they reached the whaling station. The going was still less than easy and they had some climbing still to do to negotiate ridges between them and their goal.

"Boys, this snow-slope seems to end in a precipice,

but perhaps there is no precipice. If we don't go down

we shall have to make a detour of at least five miles before

we reach level going. What shall it be?"

"Try the slope"

The waterfall at

Stromness

down which the three men had

to

climb with the use of a rope

to reach the whaling station.

At 1:30 p.m. they climbed the final ridge and saw a small whaling boat entering the bay 2,500 feet below. They hurried forward and spotted a sailing ship lying at a wharf. Tiny figures could be seen wandering about and then the whaling factory was sighted. The men paused, shook hands and congratulated each other on accomplishing their heroic journey.

The only possible way down seemed to be along a stream flowing to the sea below. They went down through the icy water, wet to their waist, shivering cold and tired. Then they heard the unwelcome sound of a waterfall. The stream went over a 30 foot fall with impassable ice-cliffs on both sides. They were too tired to look for another way down so they agreed the only way down was through the waterfall itself. They fastened their rope around a rock and slowly lowered Crean, the heaviest, into the waterfall. He completely disappeared and came out the bottom gasping for air. Shackleton went next and Worsley, the most nimble member of the party, went last. They had dropped the logbook, adze and cooker before going over the edge and once on solid ground, the items were retrieved, the only items brought out of the Antarctic.

"..... we had entered a year and a half

before with well-found ship, full equipment, and high hopes.

We had 'suffered, starved and triumphed, groveled down

yet grasped at glory, grown bigger in the bigness of the

whole.' We had seen God in His splendours, heard the

text that Nature renders. We had reached the naked soul

of man"

The whaling station, was now just a mile and a half away. They tried to smarten themselves up a little bit before entering the station, but their beards were long, their hair was matted, their clothes, tattered and stained as they hadn't been washed in nearly a year. At 3 o'clock in the afternoon of May 20th 1916, they walked into the outskirts of Stromness whaling station, as they approached the station, two small boys met them. Shackleton asked them where the manager's house was and they didn't answer, they just turned and ran from them as fast as they could. They came to the wharf where the man in charge was asked if Mr. Sorlle (the manager) was in the house.

Mr. Sorlle came out to the door and said,

"Well?"

"Don't

you know me?" I said.

"I know your voice,"

he replied doubtfully. "You're the mate of the

Daisy." (the Daisy was the last of the American

open boat whalers, it had visited South Georgia in 1913)

"My name is Shackleton," I said.

Immediately

he put out his hand and said,

"Come in. Come in."

They washed, shaved, ate and slept. Worsley boarded a whaler went to rescue the three left on the other side of South Georgia at King Haakon Bay sheltering under the upturned James Caird. During this rescue a storm blew up that had it come the day previously could have spelled disaster for the three men crossing to Stromness and consequently the whole of the crew, those on the wrong side of South Georgia and all those on Elephant Island.

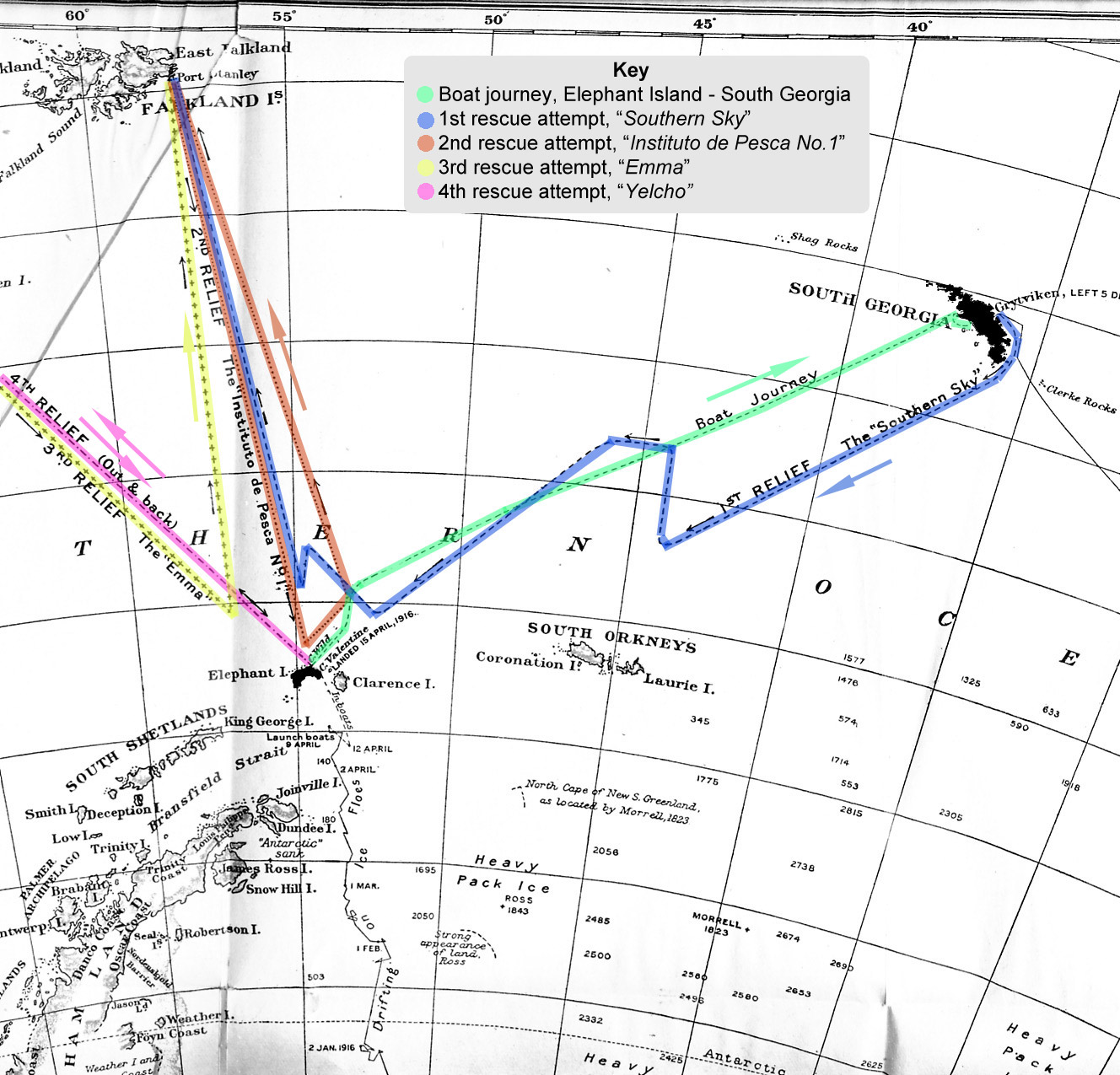

Shackleton remained at Stromness and prepared plans for the rescue of the men on Elephant Island. Shackleton, Worsley and Crean left on the British whale catcher Southern Sky that had been laid up for the winter. On the 23rd of May they were bound for Elephant Island hoping to rescue the 22 left there.

Later, Shackleton was to write in a letter

to a friend, "When we got to the whaling station, it

was the thought of all those comrades that made us so mad

with joy... We didn't so much feel safe as that they

would be saved"

Sixty miles from the island the pack ice forced them to retreat to the Falkland Islands. In the Falkland Islands, the Uruguayan Government loaned Shackleton the trawler Instituto de Pesca but once again the ice turned them away.

Shackleton went to Punta Arenas in southern Chile where British and Chilean residents donated £1,500 to Shackleton in order to charter the schooner Emma. One hundred miles north of Elephant Island the auxiliary engine broke down and thus a fourth attempt would be necessary.

The 40 yr. old wooden schooner Emma

was used for the third rescue attempt

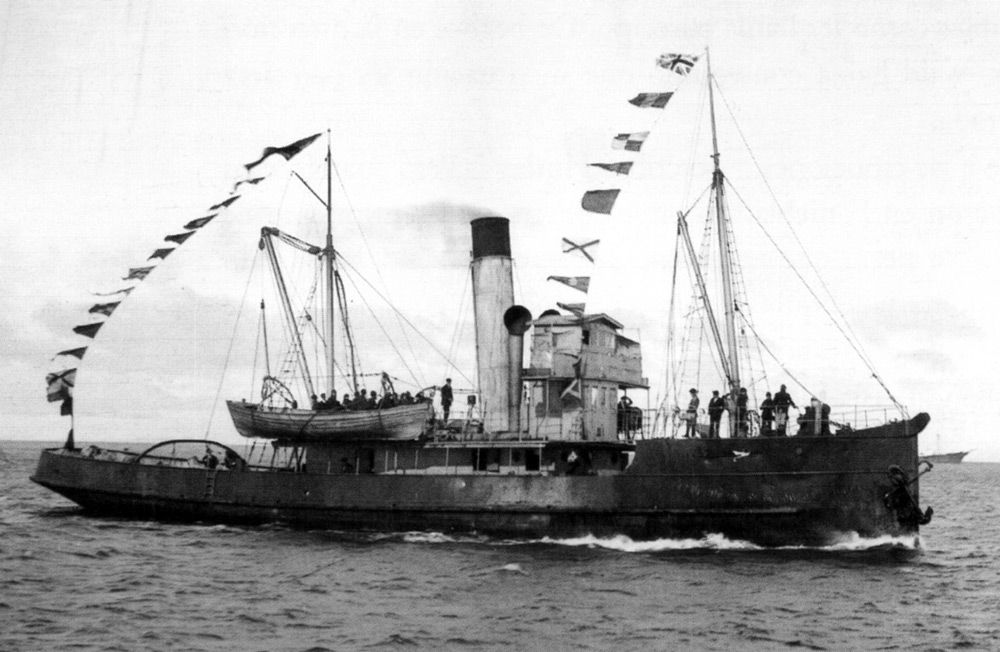

The Chilean Government now loaned the steam tug Yelcho, under the command of Captain Luis Alberto Pardo, to Shackleton.

Chilean

steam tug Yelcho. The boat that finally managed to reach

Elephant Island and rescue Shackleton's stranded men.

Chilean

steam tug Yelcho. The boat that finally managed to reach

Elephant Island and rescue Shackleton's stranded men.

It was August 30th 1916, as the steamer approached the men on Elephant Island were preparing for lunch, Marston spotted the Yelcho through an opening in the mist. He yelled, "Ship O!" but everyone thought he was announcing lunch. A few moments later those inside the "hut" heard him running forward, shouting, "Wild, there's a ship! Hadn't we better light a flare?" As they scrambled for the door, those bringing up the rear tore down the canvas walls. Wild put a hole in their last tin of fuel, soaked clothes in it, walked to the end of the spit and set them on fire.

The boat soon approached close enough for Shackleton, who was standing on the bow, to shout to Wild, "Are you all well?". Wild replied, "All safe, all well!" and the Boss replied, "Thank God!" Blackborow, since he couldn't walk, was carried to a high rock and propped up in his sleeping bag so he could view the scene. Frank Wild invited Shackleton ashore to see how they had lived on the Island, but he declined being keen to on their way as soon as possible in the light of previous failed attempts to reach the men due to ice conditions. Within an hour they were headed north to the world from which no news had been heard since October, 1914. They had survived on Elephant Island for 137 days, it was 128 days since Shackleton had left for South Georgia with his small crew on the James Caird.

Not a single man of Shackleton's original twenty-eight was lost. And though the Endurance sank in the Weddell Sea, the James Caird was brought back to England and survives to this day in Dulwich College London, a living reminder of an act of remarkable courage in the heroic age of exploration. It is preserved by the James Caird Society an official charitable organization honouring the memory of Shackleton

In 1921 Shackleton was once more drawn back to Antarctica in an attempt to map 2000 miles (3200 km) of coastline and conduct meteorological and geological research. Although he was only 47, he died of a suspected heart attack on board the Quest as she was at anchor in King Edward Cove, South Georgia. Shackleton was buried on South Georgia and his death brought to a close the "Heroic Age" of Antarctic exploration. The grave was marked by a headstone of Scottish granite in 1928 and is visited regularly by scientists and tourists to this day.

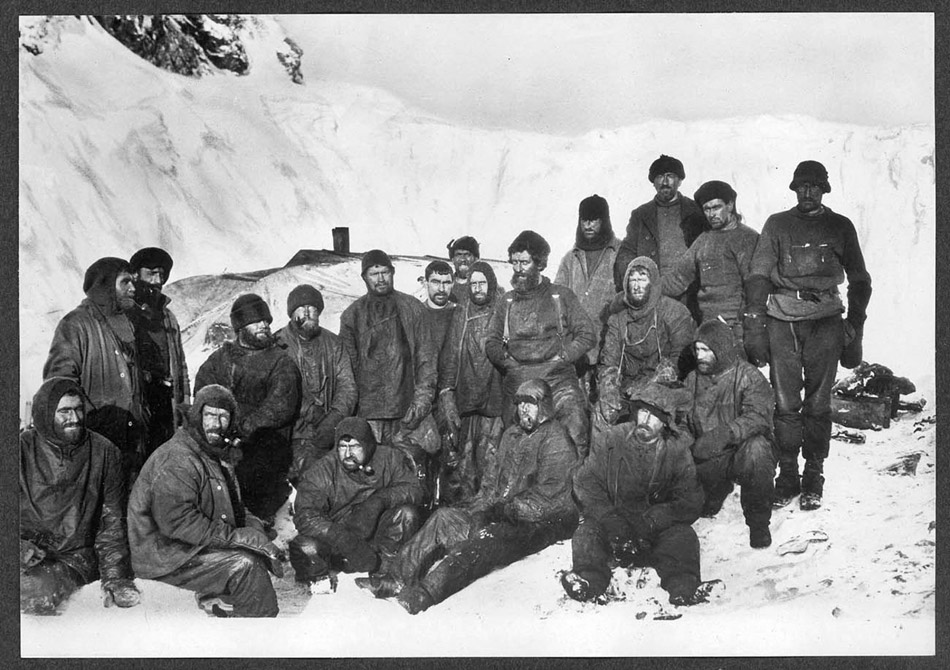

The men left behind on Elephant Island, after 3 months

The men left behind on Elephant Island, after 3 months

The "Snuggery"

the upturned lifeboats used by the men left on Elephant Island

on top of small rock walls and proofed against the weather by

tarpaulins and other cloth remnants.

The "Snuggery"

the upturned lifeboats used by the men left on Elephant Island

on top of small rock walls and proofed against the weather by

tarpaulins and other cloth remnants.

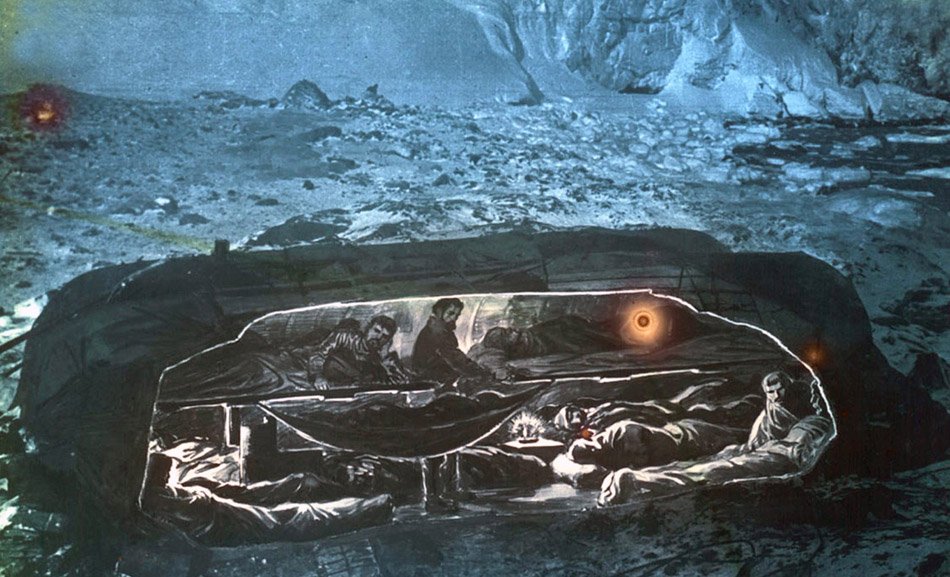

The "Snuggery" composite picture, photograph

of the outside with an artists impression of the arrangement

of the sleeping quarters on the inside.

The "Snuggery" composite picture, photograph

of the outside with an artists impression of the arrangement

of the sleeping quarters on the inside.

A

glacier at Point Wild on Elephant Island, those remaining would

have seen this as their daily back-drop while awaiting rescue

A

glacier at Point Wild on Elephant Island, those remaining would

have seen this as their daily back-drop while awaiting rescue

The

remains of Stromness whaling station pictured in 2014

The

remains of Stromness whaling station pictured in 2014

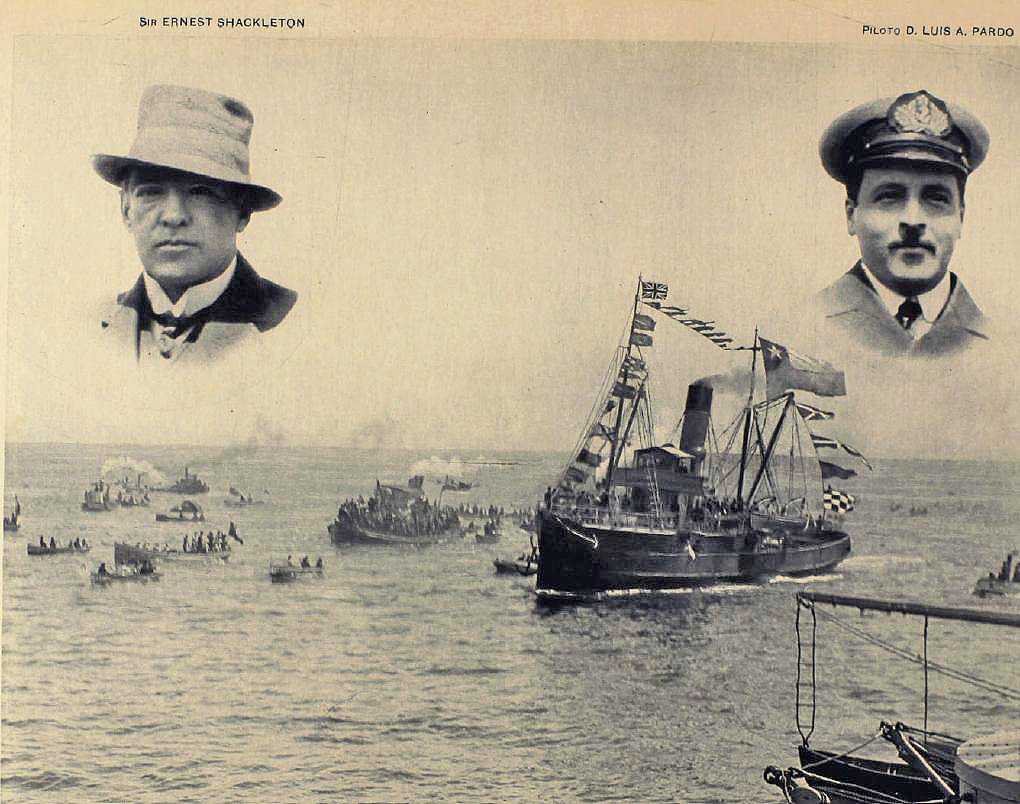

A

postcard of the Yelcho arriving back in Chile with the crew

of the Endurance, Sir Ernest Shackleton (left) and Luis Alberto

Pardo (right) the captain of the Yelcho.

A

postcard of the Yelcho arriving back in Chile with the crew

of the Endurance, Sir Ernest Shackleton (left) and Luis Alberto

Pardo (right) the captain of the Yelcho.

The

rescue voyages, starting with the James Caird from Elephant

Island to South Georgia and then three attempts to reach Elephants

Island that were turned back by heavy sea-ice before the successful

fourth attempt by the Chilean tug "Yelcho"

The

rescue voyages, starting with the James Caird from Elephant

Island to South Georgia and then three attempts to reach Elephants

Island that were turned back by heavy sea-ice before the successful

fourth attempt by the Chilean tug "Yelcho"

The

James Caird is today on permanent display in Dulwich College

London, the school attended by Ernest Shackleton between the

ages of 13 and 16

The

James Caird is today on permanent display in Dulwich College

London, the school attended by Ernest Shackleton between the

ages of 13 and 16

Picture credits, copyright pictures used by permission: Stromness - by David Stanley from Nanaimo Canada, used under Creative Commons 2.0 Generic license. / Waterfall at Stromness - by Liam Quinn from Canada, used under Creative Commons 2.0, Share and Share Alike Generic license.

Ernest Shackleton Books and Video

South - Ernest Shackleton and the Endurance Expedition (1919)

original footage - Video

Shackleton

dramatization

Kenneth Branagh (2002) - Video

Shackleton's Antarctic Adventure (2001)

IMAX dramatization - Video

The Endurance - Shackleton's Legendary Expedition (2000)

PBS NOVA, dramatization with original footage - Video

Endurance : Shackleton's Incredible Voyage

Alfred Lansing (Preface) - Book

South with Endurance: Frank Hurley - official photographer

Book

South! Ernest Shackleton Shackleton's own words

Book

Shackleton's Way: Leadership Lessons from the Great Antarctic Explorer

Book