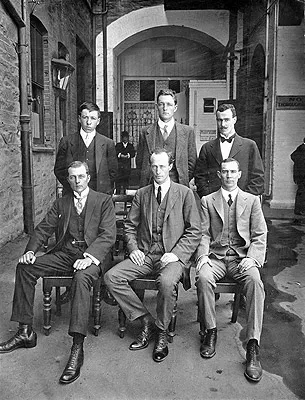

Percy Edward Correll

Biographical notes

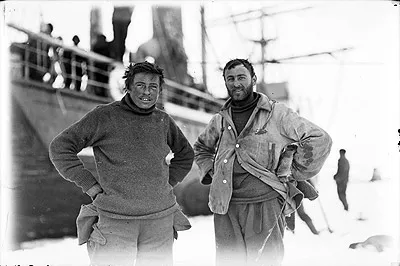

Mechanic and Assistant Physicist - Aurora 1911-1913

Single, a student in Science of the Adelaide University.

He joined the Expedition as Mechanician and Assistant Physicist.

He was a member of the Main Base Party accompanying the Eastern

Coastal Party during their sledging journey. He spent three

summers and one winter in the Antarctic, acting as colour photographer

during the final cruise of the `Aurora'.

From Appendix

1, Mawson - Heart of the Antarctic

Landmarks named after Percy Correll

Feature Name: Correll

Nunatak

Feature Type: summit

Latitude: 6735S

Longitude: 14414E

Description: A

nunatak lying within the western part of Mertz Glacier, about

13 mi S of Aurora Peak. Discovered by the AAE (1911-14) under

Douglas Mawson, who named it for Percy E. Correll, mechanic

with the expedition.

References to Percy

Correll in Mawson's book "The Home of the Blizzard"

buy USA |

buy UK |

free world delivery

-

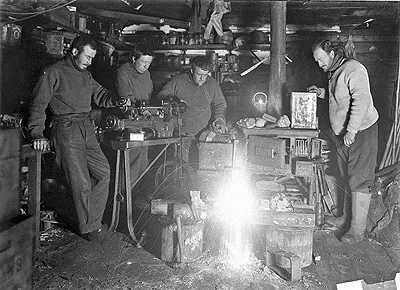

The meteorological instruments, carefully nursed and housed though they were, were bound to suffer in such a climate. Correll, who was well fitted out with a lathe and all the requirements for instrument-making, attended to repairs, doing splendid service. The anemometer gave the greatest trouble, and, before Correll had finished with it, most of the working parts had been replaced in stronger metal.

-

I remember waking up early one morning to find the Hut unusually cold. On rising, I discovered Hurley also awake, busy lighting the fire which had died out. There was no sign of Correll, the night-watchman, and we found that the last entry in the log-book had been made several hours previously. Hurley dressed in full burberrys and went out to make a search, in which he was soon successful.

It appeared that Correll, running short of coal during the early morning hours, had gone out to procure some from the stack. While he was returning to the entrance, the wind rolled him over a few times, causing him to lose his bearings. It was blowing a hurricane, the temperature was -70 F., and the drift-snow was so thick as to be wall-like in opacity. He abandoned his load of coal, and, after searching about fruitlessly for some time in the darkness, he decided to wait for dawn. Hurley found him about twenty yards from the back of the Hut.

-

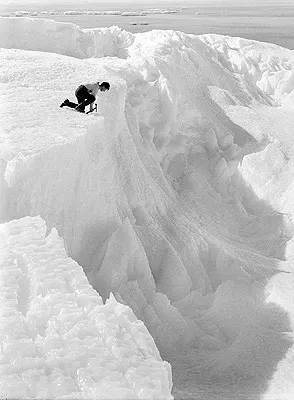

Early that day we had our first experience of the treacherous crevasse. Correll went down a fissure about three feet wide. I had jumped across it, thinking the bridge looked thin, but Correll stepped on it and went through. He dropped vertically down the full length of his harness—six feet. McLean and I soon had him out. The icy walls fell sheer for about sixty feet, where snow could be seen in the blue depths. Our respect for crevasses rapidly increased after this, and we took greater precautions, shuddering to think of the light-hearted way we had trudged over the wider ones.

-

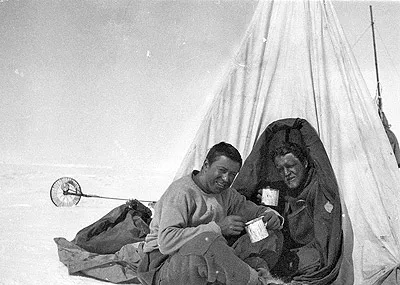

After the halt at noon the sastrugi became much larger and softer. The fog cleared at 2 P.M. and the sun came out and shone very fiercely. A very inquisitive skua gull—the first sign of life we had seen thus far—flew around the tent and settled on the snow near by. In the calm, the heat was excessive and great thirst attacked us all the afternoon, which I attempted to assuage at every halt by holding snow in my hands and licking the drops of water off my knuckles—a cold and unsatisfactory expedient. We travelled without burberrys—at that time quite a novel sensation—wearing only fleece suits and light woollen undergarments. Correll pulled for the greater part of the afternoon in underclothing alone.

-

It was obvious that this was the place for our first depot. I had decided, too, to make it the first magnetic station and the point from which to visit and explore Aurora Peak. None of us made any demur over a short halt. Correll had strained his back during the day from pulling too hard, and was troubled with a bleeding nose. My face was very sore from sunburn, with one eye swollen and almost closed, and McLean's eyes had not yet recovered from their first attack of snow-blindness.

-

The load commenced to glide so quickly as we were leaving the crest of the mountain that Correll and McLean unhitched from the hauling line and attached themselves by the alpine rope to the rear of the sledge, braking its progress. I remained harnessed in front keeping the direction. For two miles we were going downhill at a running pace and then the slope became suddenly steeper and the sledge overtook me. I had expected crevasses, in view of which I did not like all the loose rope behind me. Looking round, I shouted to the others to hold back the sledge, proceeding a few steps while doing so. The bow of the sledge was almost at my feet, when—whizz! I was dropping down through space. The length of the hauling rope was twenty-four feet, and I was at the end of it. I cannot say that "my past life flashed before me." I just had time to think "Now for the jerk—will my harness hold?" when there was a wrench, and I was hanging breathless over the blue depth. Then the most anxious moment came—I continued to descend. A glance showed me that the crevasse was only four feet wide, so the sledge could not follow me, and I knew with a thankful heart that I was safe. I only descended about two feet more, and then stopped. I knew my companions had pulled up the sledge and would be anchoring it with the ice-axe.

I had a few moments in which to take in my surroundings. Opposite to me was a vertical wall of ice, and below a beautiful blue, darkening to black in that unseen chasm. On either hand the rift of the crevasse extended, and above was the small hole in the snow bridge through which I had shot.

Soon I heard McLean calling, "Are you all right?" And I answered in what he and Correll thought an alarmingly distant voice. They started enlarging the hole to pull me out, until lumps of snow began to fall and I had to yell for mercy. Then I felt they were hauling, and slowly I rose to daylight.

-

We each described the scenery we liked best; notable always for the sunny weather and perfect calm. McLean sailed again in Sydney Harbour, Correll cycled and ran his races, I wandered in the South Australian hills or rowed in the "eights," while the snow swished round the tent and the wind roared over the wastes of ice.

Biographical information

- I am concentrating on the Polar experiences of the men involved.

Any further information or pictures visitors may have will be gratefully received.

Please email

- Paul Ward, webmaster.

What are the chances that my ancestor was an unsung part of the Heroic Age

of Antarctic Exploration?